The Patronal Tombs of the Almád Monastery

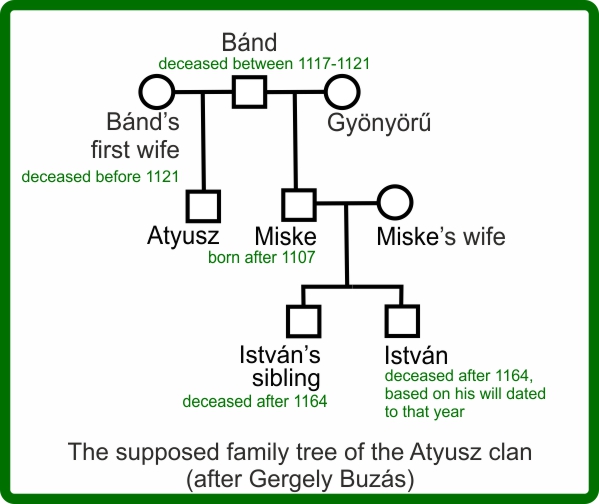

In the second half of the 11th century, privately founded monasteries began to appear in Hungary, later spreading throughout the 12th century. These were typically established by private individuals, usually nobles of comital rank (‘ispán’ in Hungarian), who created them following the model of 11th-century royal monasteries. Their primary purpose was to serve as spiritual sanctuaries and burial places for the founders and their families. Research previously referred to these as family monasteries, as the descendants of the founders later used them as burial grounds for their entire clan, and often retained them as shared family property. Among these private monasteries, the monastery built on the Almád estate of the Atyusz clan,dedicated to the Virgin Mary and All Saints, stands out due to its rich written and archaeological sources. Excavations have revealed the burials of members of the founding clan as well as those of later patronal families. Scientific studies of these graves have uniquely shed light on the burial customs of patrons during the Árpádian Age and the late Middle Ages.

The Two Burial Sites in the Monastery Church

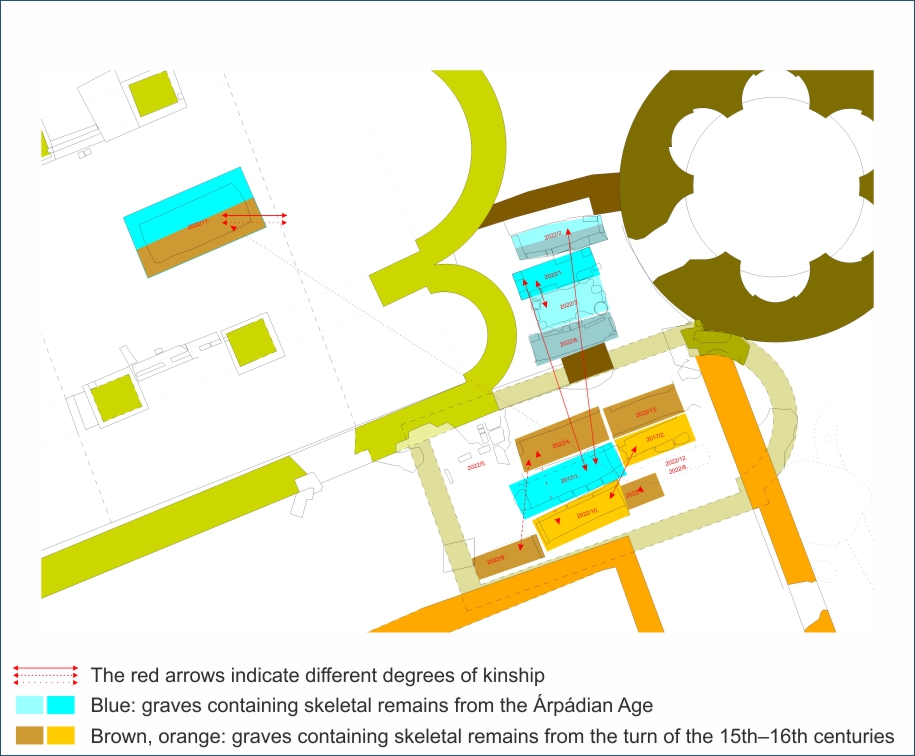

After the foundation of the monastery, two burial sites were established within its church. The first was a burial chamber constructed in the center of the church, within the monastic choir, topped with a richly decorated tomb. Although this chamber was completely looted in the 18th and 19th centuries, the bones found here were reburied in treasure-hunting pits dug on the church grounds, making their examination still possible. This burial chamber may have been built by Atyusz, the monastery’s founder, and likely served as the resting place for his descendants as well.

The second burial site was a chapel added later on to the southeastern corner of the church. This chapel is likely identifiable as the Saint Dominic Chapel mentioned in medieval sources, which was possibly constructed by Atyusz's stepmother, Gyönyörű. She is thought to have built it as a burial site for herself and to house a relic of Saint Dominic of Sora, which she brought back from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. She was buried in a tomb made of ashlar stones in front of the chapel’s altar, with her son Miske interred behind her, in a walled tomb covered by a Roman grave stele. Later, her descendants may have created additional graves within the chapel.

In the 13th century, Miske’s lineage became the wealthiest and most influential branch of the family. During this period, they likely expanded their chapel to accommodate the reburial of the bones of two ancestors from the time of Saint Stephen. However, by the 14th and 15th centuries, the clan had fallen into poverty and lost its patronal rights over the monastery, although descendants retained the privilege of being buried among their ancestors. Around this time, graves belonging to new patronal families began appearing in the monastery. The most identifiable among these are a group buried in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, who were likely relatives of the Kamicsáci Horvát family, the monastery’s owners during this period. They primarily used the chapel’s Árpádian-age graves in the southeastern section, which were emptied of their original remains, with the old bones moved to tombs in an adjacent space of the chapel. This is probably how Gyönyörű’s remains ended up in one of these graves. The only exception was Miske’s tomb, covered by a Roman gravestone in the center of the chapel, where even during this period, a member of the Atyusz clan was still buried.

impresszum

Exhibition credits

Kings, Saints, Monasteries

The world of the early Benedictines in Hungary in the light of recent scientific research

Multidisciplinary research of the HUN-REN Research Centre for the Humanities 2021-2024 (KÖ-41/2020, KÖ-29/2021, KSZF-54/2022)

Project owner: HUN-REN Research Centre for the Humanities

Project leader: Kornél Szovák

Project coordination: Balázs Gusztáv Mende

Scientific Advisory Board of the project: Balázs Balogh, Elek Benkő, László Borhy, Norbert Jeromos Mihályi OSB, Brigitta Péterváry-Szanyi, Imre Takács, Miklós Takács, Tivadar Vida

Excavation leaders: Szabolcs Balázs Nagy, Ágoston Takács

Wall research: Anna Simon

Archaeology Technicians: Vivien Gönczi, Szabolcs Molnár, Zoltán Szabó, Péter Váczi, Ernő Wolf

Consultants: Gergely Buzás, Tamás Dénesi, Csaba László, †András Végh

Institutions involved in the research presented:

St. Maurice Monastery, Bakonybél

Pannonhalma Archabbey, Pannonhalma

Benedictine Abbey of Tihany, Tihany

HUN-REN Research Centre for the Humanities Institute of Archaeology, Budapest

HUN-REN Research Centre for the Humanities Institute of Archaeogenomics, Budapest

Eötvös Loránd University Institute of Archaeological Sciences, Budapest

Isotoptech Zrt., Debrecen

Laczkó Dezső Museum, Veszprém

Hungarian National Museum King Matthias Museum, Visegrád

Bakony Natural History Museum of the Hungarian Natural History Museum, Zirc

Archaeological works, geoinformatics: Heritage Consulting Kft., Historiarch Kft., Mecenatura Bt., Work-Metall Trans Ltd., Pazirik Kft., Fent-Lent Ipari Alpin és Barlangtechnikai Kft., “Utak Mentén” Archaeological Landscape Research Group, Veszprém

Stone conservation: Péter Módi

Conservation of wall paintings: József Lángi

Restoration works: Archeolore Ltd.

Exhibition concept: Károly Belényesy, Gusztáv Balázs Mende, Péter Zsjak

Exhibition installation: Profnet Informatikai Kft.

Films, photos, 3D surveys: Pazirik Kft.

Photo of the Royal Crypt before excavation: Attila Mudrák

Photos of the abbots' gravestones, Pannonhalma: Domonkos Horváth

English translation: Barbara Szij

Further contributors: Gábor Ágoston Barkó OSB, Noémi Borbély, Gergely Buzás, Botond Heltai, István Major, Melinda Megyes, Szabolcs Balázs Nagy, Eszter Simor, Bea Szeifert, Mariann Szlavkovszky, Ágoston Takács

Communication and PR: Kinga Szőts-Rajkó

Special thanks: Lajos Patonay, Radio Dental Extra Kft.

C14

„sepultus in Tyhon iuxta lacum Valatun cum suo filio David” / “he was buried in Tihany next to Lake Balaton with his son David” (excerpt from the Pozsony Chronicle)

According to the historical records, the remains of King Andrew I (†1060) and his younger son, Duke David (†1094 (?)), are to be found in the Royal Crypt of the Benedictine monastery of Tihany. Unfortunately, DNA tests have not provided sufficient evidence to separate the bones of the royal family from the other remains from the crypt, which have been mixed up over the centuries and have been severely depleted. Therefore, the researchers had to choose another method to authenticate the supposed royal remains.

After the excavations carried out in 1953, the bones found earlier in the crypt, which had not been discovered in their original position, were reburied with the newly discovered remains in 3 wooden caskets in the concrete frame created in the central tomb, on which the tombstone with a processional cross was placed on top of a few rows of bricks.

The ceremonial opening of this tomb took place as the first step in the authentication excavation of 2021. The poor quality of the wooden caskets in the middle of the tomb revealed skeletal remains that previous research had suggested were the remains of the earliest burials in the crypt. DNA analysis of the blackened, poorly preserved and fragmentary bones was carried out in parallel with the determination of their absolute age, with the assumption that the results would confirm their 11th century origin.

Radiocarbon dating

The so-called radiocarbon dating method, which can be used in archaeological research to date objects from the last 50 000 years, has provided a useful way of dating burials.

The method is based on the measurement of the current concentration of the radioactive isotope of carbon (14C), which is in equilibrium with the environment in a living organism until death, in a constant ratio with the stable isotope of carbon (12C). At the moment of death, however, this equilibrium is upset and radioactive decay becomes the dominant process, with the amount of 14C halving at regular intervals (~5700 years) and thus its concentration decreasing. Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) is the commonly used method to determine the radiocarbon age of a sample, in BP (BeforePresent), counting back from 1950. This primary data is converted into a calibrated or calendar age using the so-called calibration curve. This is denoted by the cal. term assigned to the time scale, which in our case could be given in the time elapsed since the birth of Christ (AD, or Anno Domini). For metrological reasons, the age datum obtained in this study is never a specific year (the year of death), but a larger range of up to a hundred years, within which probability values are assigned to the possible year of death. In the case of multi-sample series, the age data obtained can be further refined by mathematical models.

A few grams of bone samples from different anatomical parts, taken in parallel for DNA analysis, are lab coded. Only this coded data and the information about the sampling are sent to the laboratories carrying out the tests, i.e. the data obtained are anonymous during the test, and only at the very end are they matched with the bones. In priority cases, the analysis is carried out in parallel, starting from the same samples, in several laboratories.

The radiocarbon analysis of the bone remains recovered from Casket 2 at Tihany was carried out by several laboratories. Based on the combined data of the radiocarbon analyses carried out in Mannheim, Poznan and Debrecen in parallel, some of the bone remains recovered from Casket 2 certainly represent the earliest period of use of the crypt, the 11th century. However, it can be matched to the years of death of the king and his son from a chronological point of view only. The results obtained have well isolated the later remains, linking them to burials from the 15th to 18th centuries. The skull and skeletal remains, dated to the 11th century, may belong to the remains of King Andrew and his son Duke David.

LIDAR

WHAT IS A HISTORIC LANDSCAPE?

To formulate the subject of our research is only seemingly simple, since the landscape as we know it today has essentially become so because the natural environment has been continuously influenced by human activities from the earliest times. And these influences, whether they are traces of agriculture, settlements, cemeteries, roads, mines, etc., form interconnected and complex networks.

HOW TO RESEARCH IT?

Research on specific (even historical) layers of the landscape, like traditional archaeological excavation, is essentially based on the identification, processing and organization of visual information. However, it is naturally fraught with limitations because of the methods of observation. Whether we have a good aerial photograph, satellite image, old map, etc., the only landscape that can really become a 'historic landscape' is the one that we succeed in noticing, since what we cannot see or notice cannot be recorded, measured or discussed, therefore, it is basically non-existent. Today, however, LiDAR technology represents a real turning point in the exploration of the layers of the landscape.

WHAT IS LIDAR?

The term LiDAR itself is quite a mouthful, short for Light Detection and Ranging, a technique that uses millions of laser pulses typically emitted by low-altitude flying devices mounted on drones, helicopters or airplanes. It's actually a specialized data collection, or scanning if you prefer. Thanks to the fact that the device emits an incredibly high number of signals per second, even in the densest forest, enough laser beams can actually reach the ground to obtain information about the original terrain surface, even in areas with lush vegetation. Just think of the sunlight filtering through the leaves of trees in a dense forest – this is how one should imagine a laser scanning the ground.

CAN WE SEE UNDER THE GROUND WITH IT?

Although the laser does not penetrate the ground, it can use special processing techniques to make visible to us the area in which the remains of the historical landscape we are researching can still be found and identified. Although the vegetation itself is surveyed during the operation, we can digitally remove the ‘distracting’ details and create an original, ‘stripped down’ topographic map of the area, be it the Tihany Peninsula or the High Bakony Hills.

Family histories from the ruins of the Benedictine monastery in Almád

The Monastery of Almád

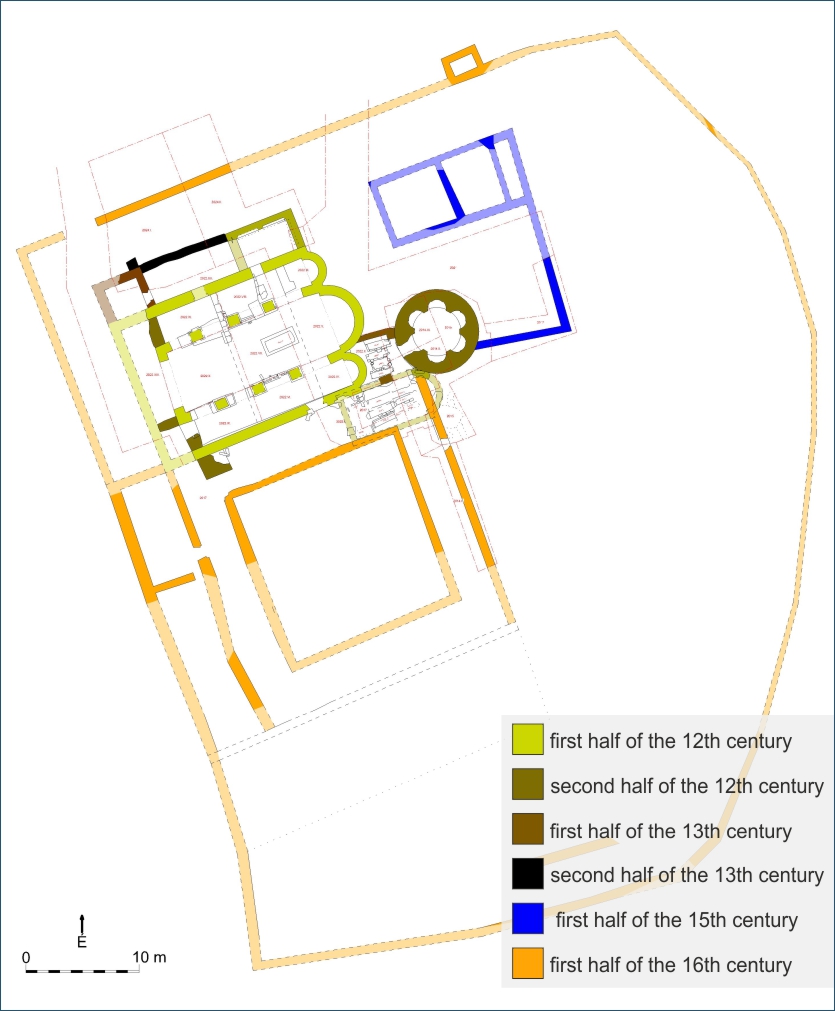

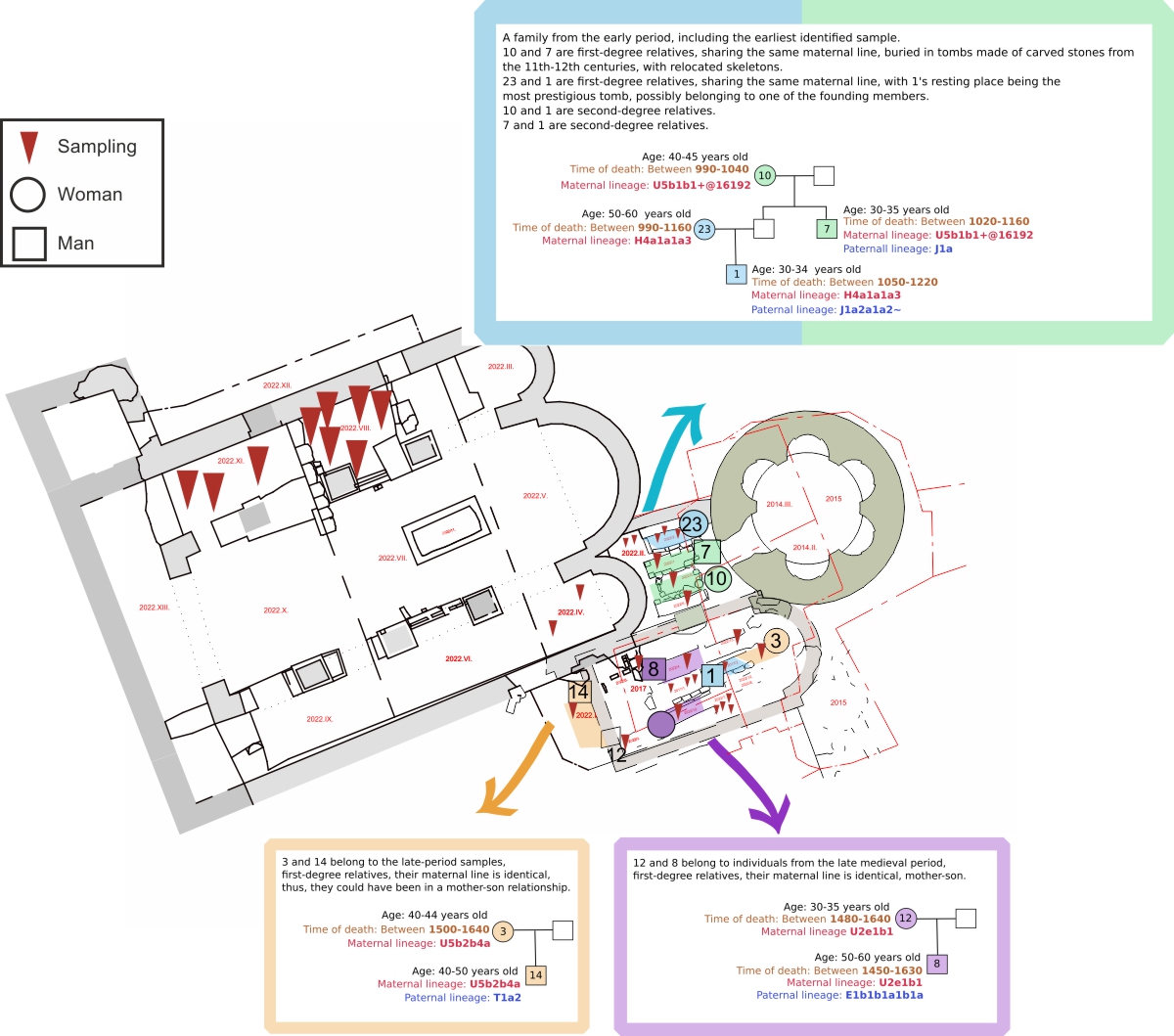

The history of the Almád Monastery, founded by the Atyusz clan, is well-documented, particularly through the 1121 founding charter issued by a nobleman named Atyusz. Excavations near Monostorapáti revealed that a member of the clan had built a church in the area as early as the 11th century. The basilica, constructed between 1117 and 1121, underwent several reconstructions, with members of the patron family buried in the central crypt and southeastern chapels. By the late medieval period, the monastery came under the influence of the Horvát family, owners of the neighboring Nagyvázsony estate. Monastic life ceased in the 1540s, and the structure was dismantled in 1552. During the 18th and 19th centuries, treasure hunting was intensive among the ruins; fortunately, human remains that were removed were carefully reinterred.

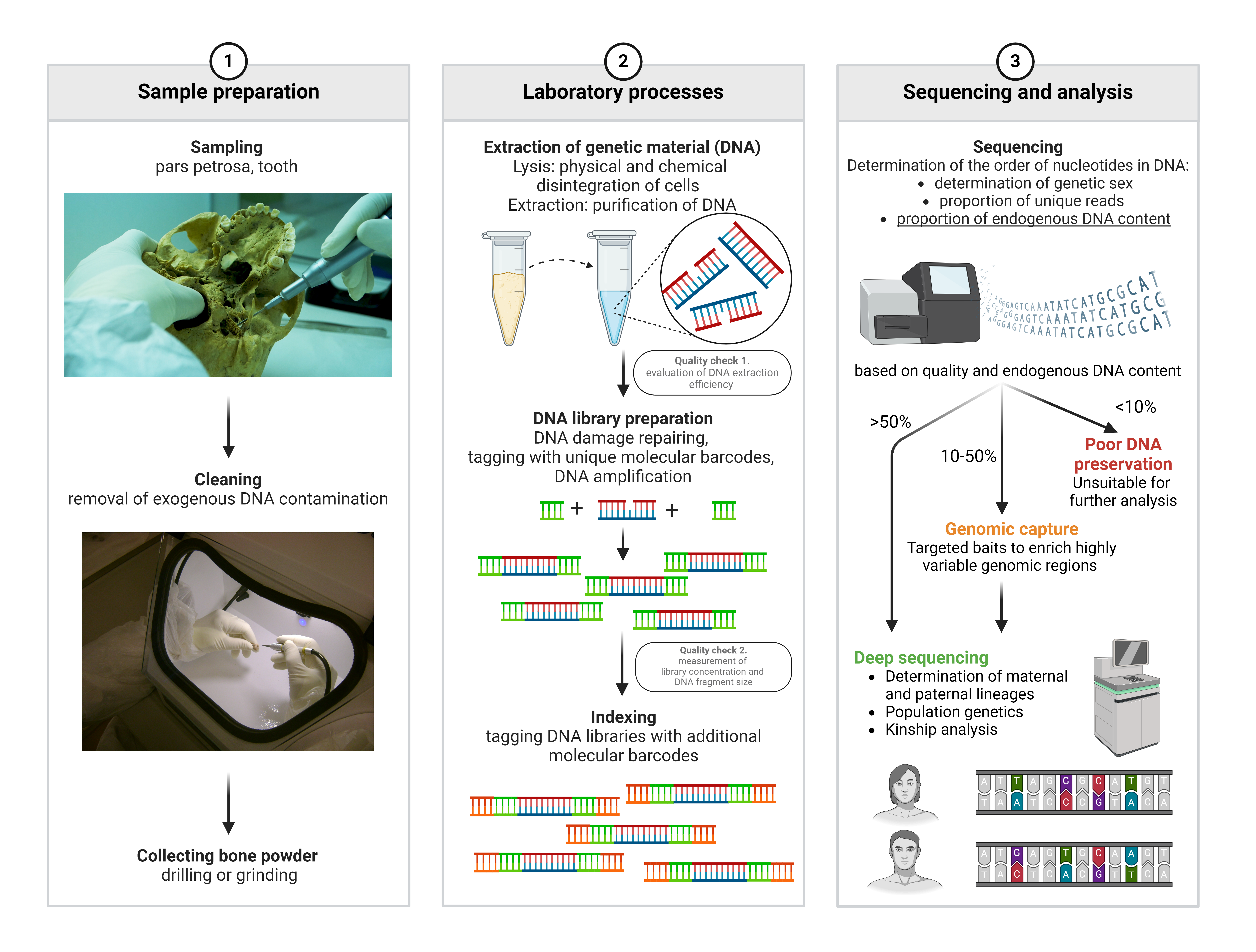

Archaeological research on the patron family’s tombs, along with written sources related to the monastery, have enabled the potential identification of some individuals buried there, allowing for a reconstruction of burial customs and choices of burial sites. This work required anthropological analysis, radiocarbon dating of human remains, and kinship analysis among those buried.

Genetic analysis of kinship relations

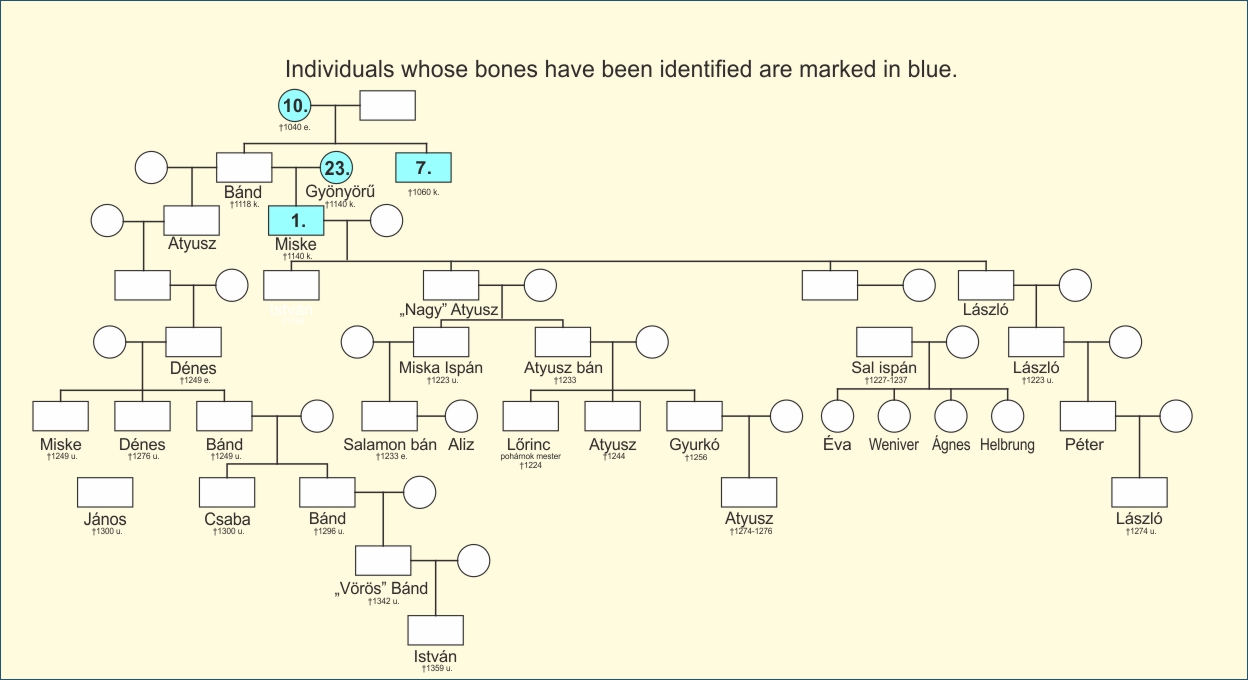

Human remains from 34 individuals discovered in the Almád Monastery excavation were transferred to the Archaeogenomics Institute RCH HUN-REN for laboratory processing and genetic analysis. The primary objective of these studies is to map kinship relations, comparing findings against the hypothesized family tree of the Atyusz clan, reconstructed from historical sources.

Key Research Findings

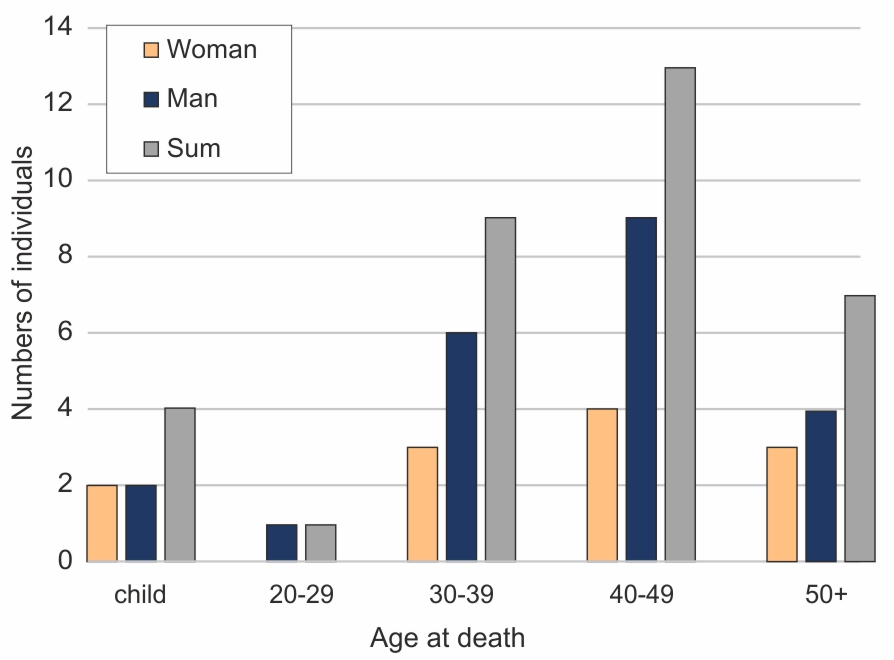

A total of 12 women and 22 men were identified (through anthropological and genetic analyses), including bone remains of four children.

Based on radiocarbon dating of 25 human remains, the samples fall into two main groups: one from the 10th-13th centuries and another from the 15th-17th centuries, with at least two individuals passing away before the monastery’s founding.

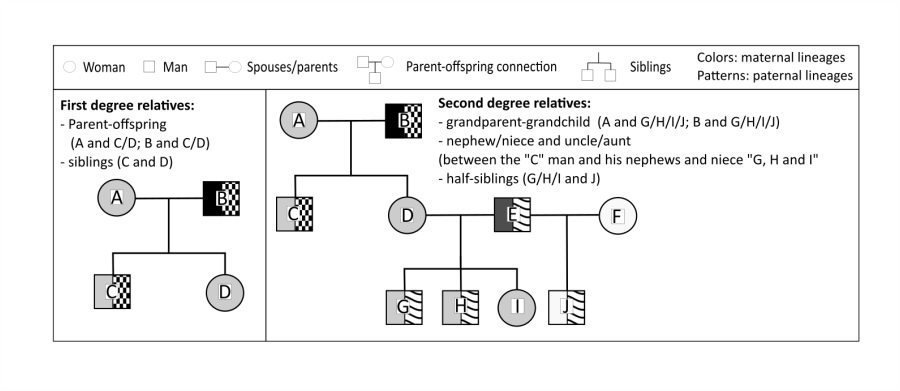

Among the deceased, six individuals were identified as first-degree relatives, and eight pairs of second-degree kinship relations were also established.

Despite kinship ties, the group is diverse, especially regarding maternal lineages.

Mapping Kinship: Integrating Insights Across Disciplines

Kinship determination is conducted by analyzing information from the whole genome, while also incorporating data from maternal lineage (mitochondrial DNA) and paternal lineage (Y-chromosomal DNA). Although matches in these markers do not necessarily indicate close kinship—as they can remain consistent over centuries—they are essential in determining the direction of the relationship when the degree of kinship is known. For example, if genetic analysis suggests a first-degree, parent-child relationship between an adult male and an adult female, and their maternal lineage matches, it is likely that the female was the mother of the male.

Anthropological and absolute chronological data further support the construction of the family tree. For instance, if a parent-child relationship is indicated by genetic data between an adult and a young child identified through anthropological study, the direction of the relationship is clearly defined.

Genetic correlations of individuals buried in the monastery of Almád

Pigmentation Analysis

Genetic analysis enables the examination of skin, hair, and eye color.

The people buried in the Almád Monastery are characterized by medium brown skin tones and likely brown hair shades (neither blonde nor black), with some individuals having curly hair. Among those analyzed, lighter eye colors were observed in a few cases, though no blue-eyed individuals were identified.

Conclusions

The genetic findings and available historical data suggest the following hypotheses:

Individual 1 (buried in Grave 2017/2/1) may be identified as Miske of the Atyusz clan.

The mother of the individual buried in Grave 1, identified as Individual 23, could correspond to Miske’s mother, known as Gyönyörű, mentioned in historical records.

The paternal lineage characteristic of the male line of the Atyusz clan may belong to haplogroup J1a2a.

This research remains ongoing, with the next step focusing on examining the broader kinship network of individuals buried at the monastery, using insights derived from their whole genomes.