Újkori sírok

Early modern graves

Early modern graves

Tihany végvári funkciója a 17. század végére megszűnt és 1701-től újra bencések költöztek a megrozzant apátság falai közé. Ebben az időben az altemplomot használták templomként, és ide is temetkeztek. Ehhez a korszakhoz köthető a legtöbb újkori sír, köztük a feltárt maradványok alapján két apát temetkezése is, akik az Altenburgból ideköltöző szerzetesközösséget vezethették, név szerint Regondi Rajmund és Reyser Ámánd. Később már a templom hajója alatt kialakított barokk kriptát használták, ezért annak megépülte után már egészen biztosan nem temettek itt el senkit.

Early modern graves

Tihany's function as a border fortress ended at the end of the 17th century and from 1701 Benedictine monks started to return to the crumbling abbey. At this time the crypt was used as a church and was also used for burial. Most of the modern graves are from this period, including, according to the remains excavated, the burials of two abbots who may have led the monastic community that moved here from Altenburg, namely Raymundus Regondi and Amand Reyser. Later, the Baroque crypt under the nave of the church was used, so it is quite certain that no one was buried in the medieval crypt after its construction.

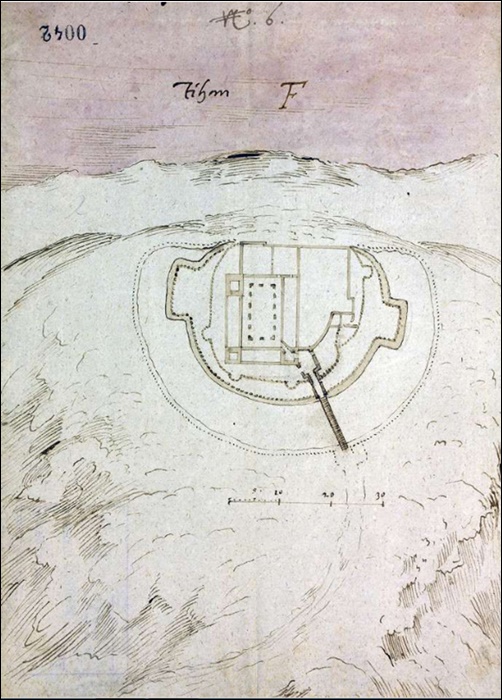

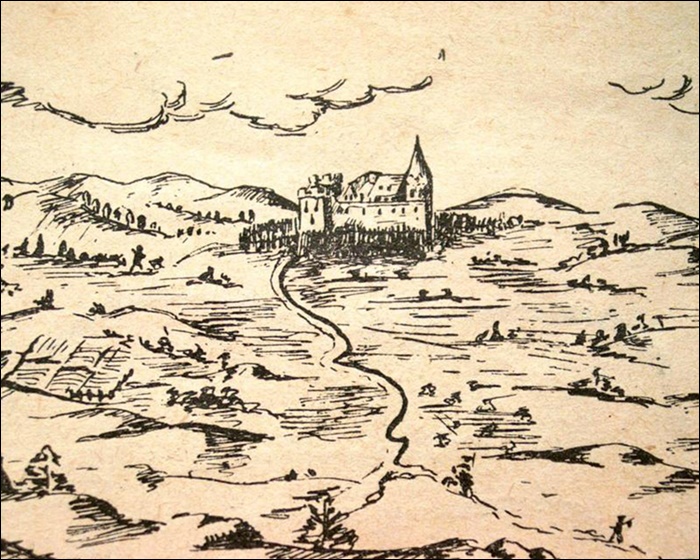

Végvári idők

The Ottoman–Hungarian wars

The Ottoman–Hungarian wars

A 16. század közepétől a 17. század végéig tartó időszakban, amit általában csak a török kornak hívunk, az apátság élete is gyökeresen megváltozott. A szerzetesek elmenekültek, helyükre végvári katonák érkeztek, az apátságot megerődítették, és ez is része lett az ország még nem elfoglalt nyugati részét védő végvárrendszernek. Az altemplomot ekkor szénaraktárként használták, és minden bizonnyal ennek az időszaknak az emléke az a több száz, vasból, illetve ólomból készült puska- és pisztolygolyó, amelyek az ásatás során a templom földjéből előkerültek. Amennyiben hihetünk a 16-17. századi forrásoknak, amelyek szerint raktár volt itt, nem valószínű, hogy temetkeztek is volna ide.

The Ottoman–Hungarian wars

In the period from the mid-16th to the end of the 17th century, which is usually referred to as the Ottoman era, the life of the abbey changed radically. The monks fled the abbey, and they were replaced by soldiers, while the abbey was fortified and became part of the border fortress system protecting the unoccupied western part of the country. The crypt was then used as hay storage. The hundreds of iron and lead musket balls and pistol bullets recovered from the crypt's ground during the excavations are certainly a reminder of this period. If the sources from the 16th and 17th centuries are to be believed, which say that the crypt was turned into a storage room, it is unlikely that it was also used as a burial place.

A király sírja

The Tomb of the king

The Tomb of the king

I. András királyt halála után az általa ebből a célból alapított kolostorban temették el. Eredeti síremlékéről nem sokat tudunk. A fennmaradt, 11. századi, keresztet ábrázoló márvány sírkőről az ásatás során bebizonyosodott, hogy nem a királyi síron volt eredetileg, ugyanis semmilyen irányban nem illeszkedett a sír méreteihez, viszont annál inkább a déli mellékhajóban lévő sírhoz. A legkorábbi leírások a 17. századból az alapító vörösmészkő síremlékéről szólnak. Ez a megállapítás, az ásatáson a sírnál feltárt több periódusú falak, valamint az, hogy az altemplom földjében több, 15. század első felére keltezhető pénz került elő, arra utal, hogy ebben az időben felújították az alapító sírját, és az annak helyet adó altemplomot is, hiszen a megmaradt falképtöredékek is ebből az időszakból származnak. Ez a sír állhatott itt a 18. század elejéig, amikor a kolostor felújítása során valószínűleg megsemmisült, és csak a két, padlóba süllyesztett fehér márvány sírkő maradt meg. Ezeket Rómer Flóris bencés szerzetes még látta, a 20. századra azonban csak a díszesebb maradt meg, ami összekapcsolódott az alapító I. András személyével.

The Tomb of the king

After his death, King Andrew I was buried in the monastery he founded for this purpose. Not much is known about his original tomb. The most recent excavation has revealed that the surviving 11th-century marble tombstone with a cross did not originally belong to the royal tomb, as it did not fit in any direction with the dimensions of the grave, but rather with the grave in the southern aisle. The earliest descriptions of the red limestone tomb of the founder date from the 17th century. This finding, together with the excavation of multi-period walls around the tomb as well as the discovery of several coins in the ground of the crypt dating from the first half of the 15th century, suggests that the founder's tomb and the crypt were renovated at this time. This is also supported by the remaining wall painting fragments from this period. The renewed tomb may have stood here until the early 18th century, when it was probably destroyed during the renovation of the monastery, leaving only the two white marble tombstones sunk into the floor. The Benedictine monk and archaeologist Flóris Rómer has recorded seeing both of them, but by the 20th century only the more ornate one had survived, and it has increasingly been associated with Andrew I.

Középkori sírok az altemplomban

Medieval graves in the crypt

Medieval graves in the crypt

Az ásatás során közel húsz sírgödör lett feltárva, azonban valószínűleg ennél is több ember nyugodott itt az évszázadok során. Eredetileg azonban mindössze három személy örök nyughelyének szánták az altemplomot. Elsőként az alapító királyt, I. Andrást (1046–-1060) temették el. Övé volt a fő sírhely, a középső hajóban a keletről számított második és harmadik pillérpár között. Sírja biztosan díszes volt, és kiemelkedett a környezetéből, erről árulkodnak a pillérek lábazatai is, amelyeknek sír felé eső részét lefaragták. 1090 körül Dávid herceget, I. András fiát is itt temették el, az övé lehetett a déli mellékhajóban, a királyi sírral egyvonalban lévő falazott sír, és ezt fedhette a ma is ismert márvány sírkő. A harmadik, az északi mellékhajóban lévő sírba eltemetett személy kiléte kérdéses, de a legvalószínűbb, hogy I. András feleségét, a kijevi Anasztázia hercegnőt temették ide.

Medieval graves in the crypt

The excavation has uncovered around twenty graves, but it is likely that even more people have been buried here over the centuries. Originally, however, the crypt was only intended to be the final resting place of three people. The first to be buried was the founding king, Andrew I (1046–1060). He had the main burial place, in the central nave between the second and third pair of pillars from the east. His tomb must have been ornate and stood out from its surroundings, as the plinths of the pillars, whose part facing the tomb has been cut away, testify. Around 1090, Prince David, son of Andrew I, was buried here, and he may have been buried in the masonry tomb in the south aisle, in line with the royal tomb, and it may have been covered by the marble tombstone that we know today. There is still some debate about the identity of the third person buried in the tomb in the north aisle, but it is most likely that the wife of Andrew I, Princess Anastasia of Kiev, was buried here.

Falképek az altemplomban

Wall paintings in the crypt

Wall paintings in the crypt

Már a 11. században díszes festett falai lehettek a térnek, azonban ebből mára nem maradt semmi, csak néhány kisebb felületen az alsó, fehérre vakolt felület. Később, a 15. század közepén újra kifestették a teret. Ennek a keleti falon a középső ablak alatt néhány tenyérnyi maradványa őrződött meg korunkra. A végvári időkben ezt láthatták az itt állomásozó katonák. A barokk korban minden bizonnyal újra kifestették a falakat, erről azonban nem sokat tudunk. A 19. század végén historizáló kifestést kapott az egész tér, amelyet az 1953-as felújítás során eltávolítottak, és aminek töredékei a 2021-es ásatáson előkerültek. Leglátványosabb része a boltozat sötétkék festése volt, amelyen kis, aranyozott csillagok jelentek meg.

Wall paintings in the crypt

Already in the 11th century, the crypt may have had ornate painted walls, but today nothing remains of this, except the white plastered underlayers on some small areas. Later, in the mid-15th century, the walls were repainted. A few palm-sized fragments of this remain on the east wall under the central window. The soldiers stationed here during the Ottoman–Hungarian wars were the last ones to see these paintings. In the Baroque period, the walls were certainly repainted, but not much is known about this. At the end of the 19th century, the whole space was painted in a historicist style, which was removed during the 1953 renovation, and fragments of which were unearthed during the 2021 excavation. The most spectacular part was the dark blue painting of the vault, which was scattered with small gilded stars.