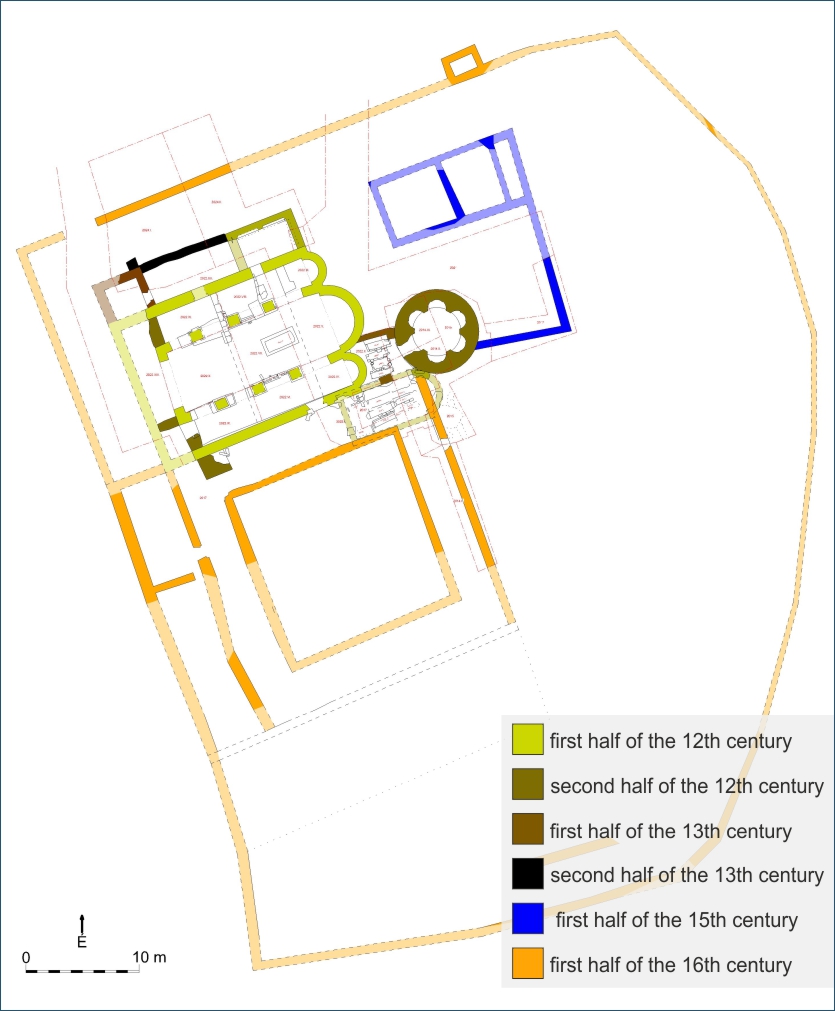

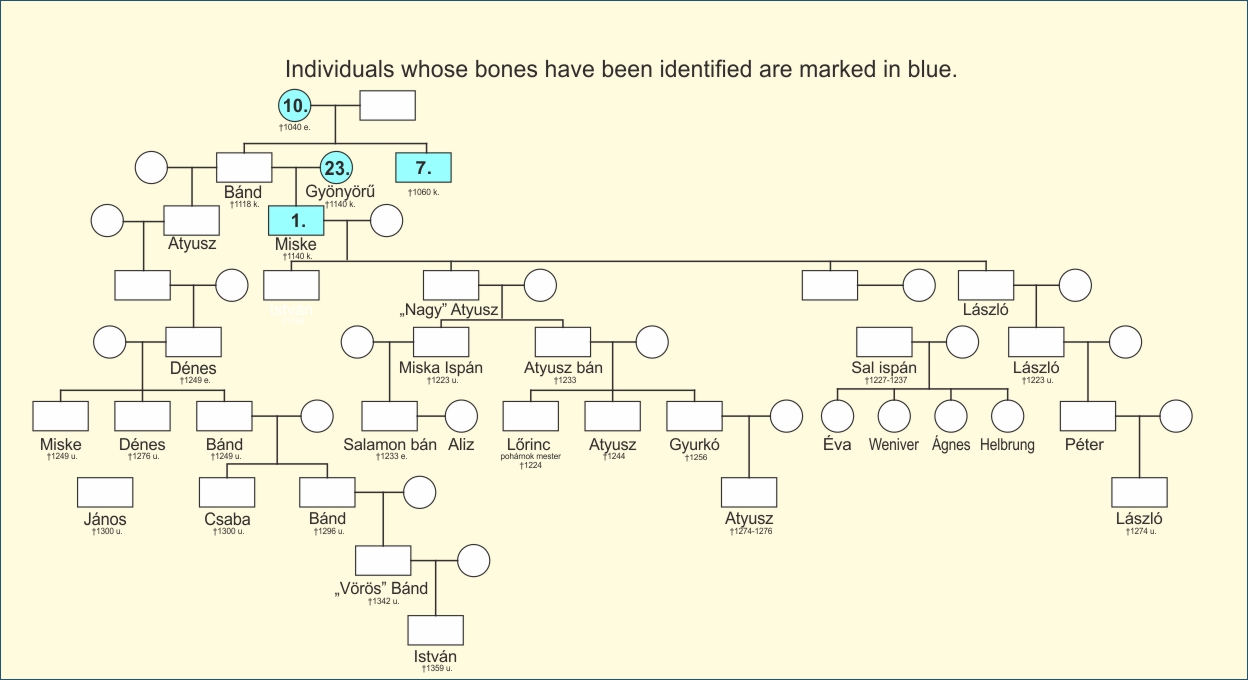

In the second half of the 11th century, privately founded monasteries began to appear in Hungary, later spreading throughout the 12th century. These were typically established by private individuals, usually nobles of comital rank (‘ispán’ in Hungarian), who created them following the model of 11th-century royal monasteries. Their primary purpose was to serve as spiritual sanctuaries and burial places for the founders and their families. Research previously referred to these as family monasteries, as the descendants of the founders later used them as burial grounds for their entire clan, and often retained them as shared family property. Among these private monasteries, the monastery built on the Almád estate of the Atyusz clan,dedicated to the Virgin Mary and All Saints, stands out due to its rich written and archaeological sources. Excavations have revealed the burials of members of the founding clan as well as those of later patronal families. Scientific studies of these graves have uniquely shed light on the burial customs of patrons during the Árpádian Age and the late Middle Ages.

The Two Burial Sites in the Monastery Church

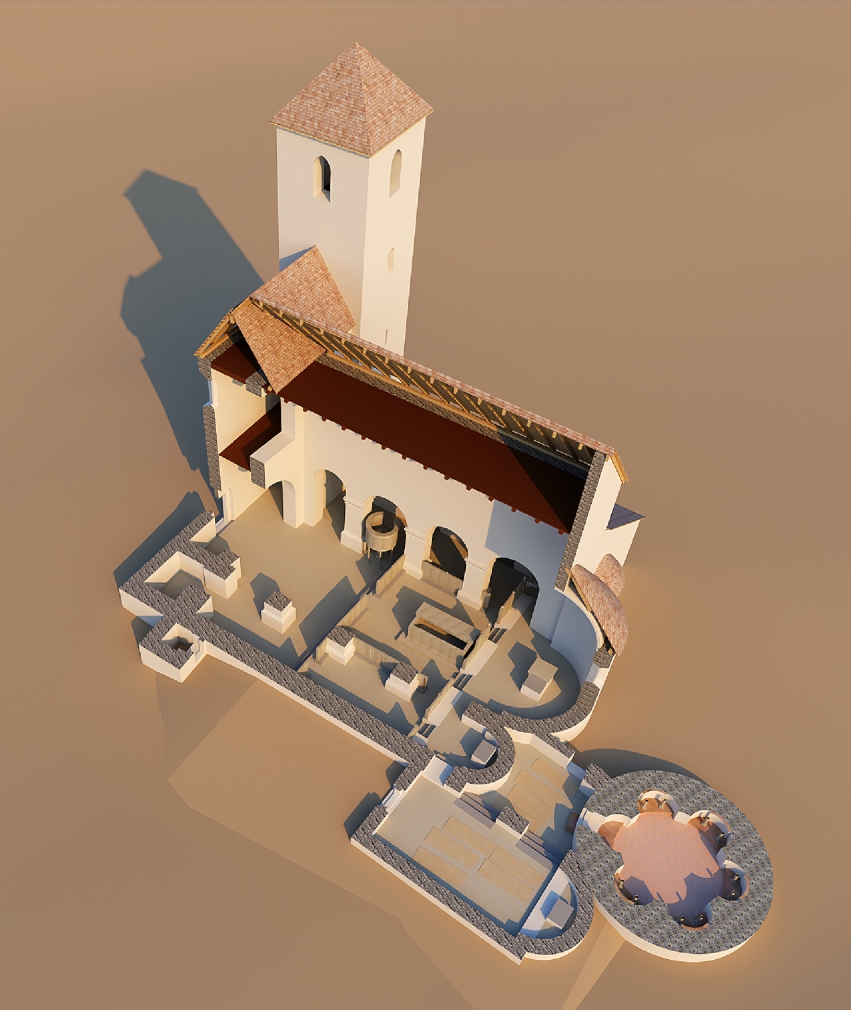

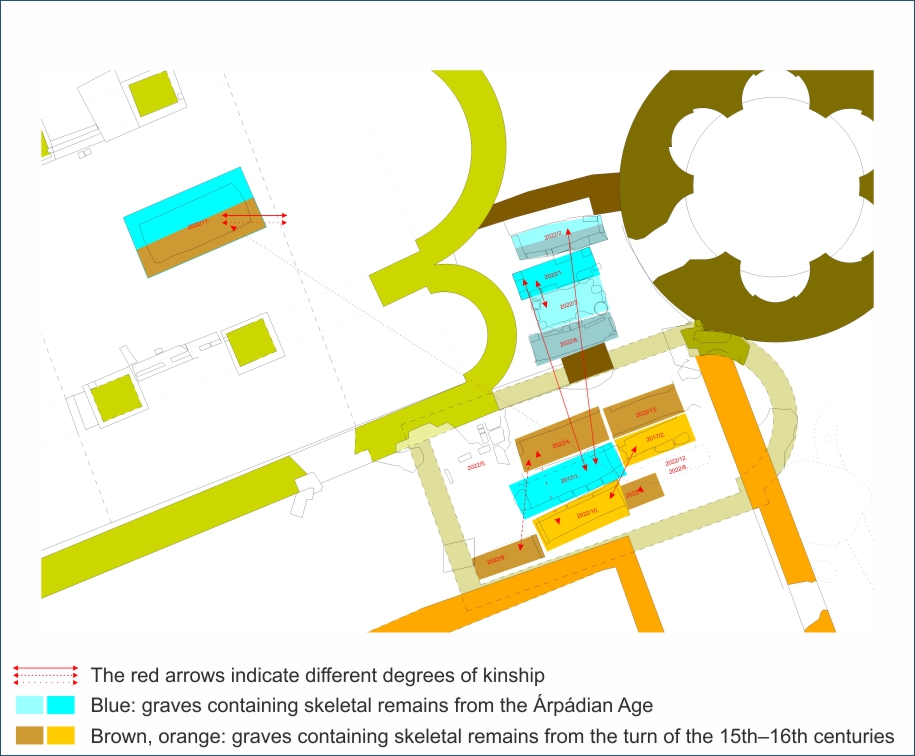

After the foundation of the monastery, two burial sites were established within its church. The first was a burial chamber constructed in the center of the church, within the monastic choir, topped with a richly decorated tomb. Although this chamber was completely looted in the 18th and 19th centuries, the bones found here were reburied in treasure-hunting pits dug on the church grounds, making their examination still possible. This burial chamber may have been built by Atyusz, the monastery’s founder, and likely served as the resting place for his descendants as well.

The second burial site was a chapel added later on to the southeastern corner of the church. This chapel is likely identifiable as the Saint Dominic Chapel mentioned in medieval sources, which was possibly constructed by Atyusz's stepmother, Gyönyörű. She is thought to have built it as a burial site for herself and to house a relic of Saint Dominic of Sora, which she brought back from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. She was buried in a tomb made of ashlar stones in front of the chapel’s altar, with her son Miske interred behind her, in a walled tomb covered by a Roman grave stele. Later, her descendants may have created additional graves within the chapel.

In the 13th century, Miske’s lineage became the wealthiest and most influential branch of the family. During this period, they likely expanded their chapel to accommodate the reburial of the bones of two ancestors from the time of Saint Stephen. However, by the 14th and 15th centuries, the clan had fallen into poverty and lost its patronal rights over the monastery, although descendants retained the privilege of being buried among their ancestors. Around this time, graves belonging to new patronal families began appearing in the monastery. The most identifiable among these are a group buried in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, who were likely relatives of the Kamicsáci Horvát family, the monastery’s owners during this period. They primarily used the chapel’s Árpádian-age graves in the southeastern section, which were emptied of their original remains, with the old bones moved to tombs in an adjacent space of the chapel. This is probably how Gyönyörű’s remains ended up in one of these graves. The only exception was Miske’s tomb, covered by a Roman gravestone in the center of the chapel, where even during this period, a member of the Atyusz clan was still buried.