A kerengőudvar (11)

The cloister courtyard (11)

The cloister courtyard (11)

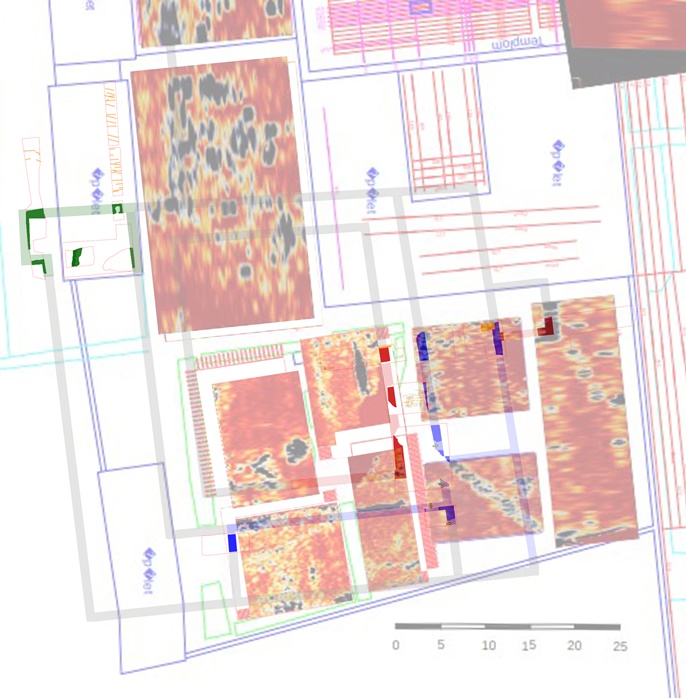

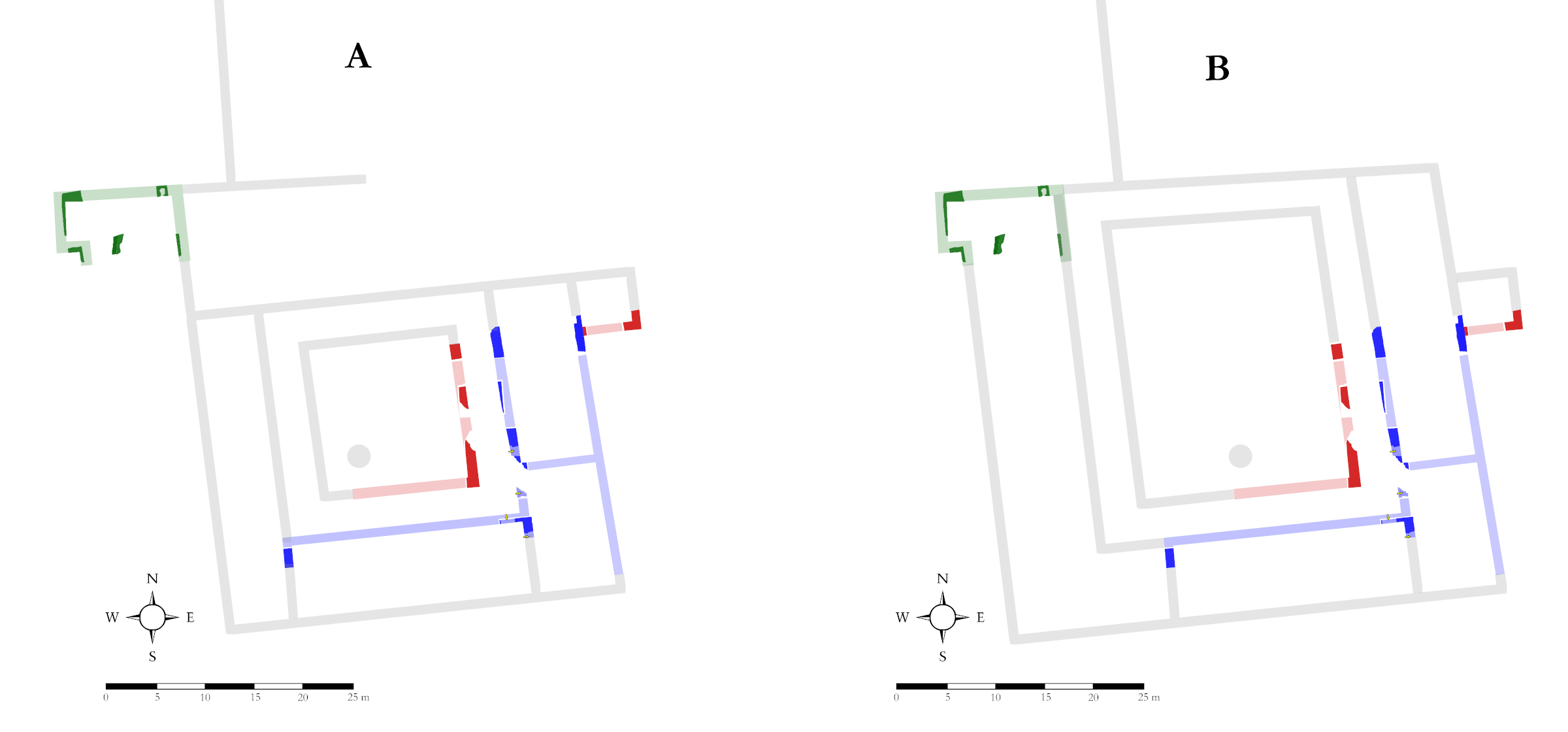

A négy oldalról kerengőfolyosó által övezett udvart csak igen kis felületen kutattuk, annyit azonban így is igazolni lehetett, hogy a kerengő mellett ez is helyet biztosított korai temetkezéseknek. Az udvar területén feltárt sírban egy valamikor 1030-1160 között elhunyt férfit temettek el. A közelében talált szórvány koponyatöredék és egyéb jelek arra utalnak, hogy a sír környezetében további temetkezésekkel is számolnunk kell. Ahol most állunk, az udvar déli szélén a geofizikai mérések egy közel kör alakú, rendkívül határozott anomáliát jeleztek. Könnyen elképzelhető, hogy itt volt a monostor udvari kútja. Elhelyezkedése jellemző a szerzetesi építészetre, hiszen a konyhát és ebédlőtermet általában a déli szárnyban alakították ki, a kutat pedig – gyakorlati okokból – sokszor ezek közelében.

The cloister courtyard (11)

The courtyard, surrounded on four sides by a cloister corridor, was only explored in a very small area, but it was possible to confirm that it was also a place for early burials. A man who died sometime between 1030 and 1160 was buried in a grave excavated in the courtyard. The scattered skull fragments and other evidence found nearby suggest that there were other burials in the area around the grave. Where we are standing now, at the southern edge of the courtyard, geophysical measurements have indicated a very defined anomaly in the shape of a circular structure. It is easy to imagine that this was the site of the monastery's well. Its location is typical of monastic architecture, since the kitchen and dining room were usually located in the south wing, and the well was often located next to them for practical reasons.

A nyugati szárny nyomában (10)

Tracing the west wing (10)

Tracing the west wing (10)

Ezen a helyen azzal a kifejezett céllal kezdtünk régészeti feltárásba, hogy azonosítsuk a monostor nyugati épületszárnyát, s ezáltal meghatározhassuk az épületegyüttes egykori kiterjedését. A napvilágra került kőfal azonban minden valószínűség szerint a déli szárny egyik válaszfala, így kiinduló kérdésünkre nem kaptunk választ. Ennek ellenére lehetnek megalapozott sejtéseink a nyugati szárny elhelyezkedéséről, ugyanis 2010-ben Rainer Pál azonosította egy olyan középkori épület kőfalait, mely jól illeszkedik a most feltárt falak és a geofizikai mérések által adódó alaprajzi rendszerbe. Ha feltételezésünk helyes, akkor a Rainer-féle falak már a rendház északi oldalán álló templom nyugati végződését jelzik. Másik lehetőség szerint ezek a falak a monostor nyugati szárnyának északi végét jelentik.

Tracing the west wing (10)

Archaeological excavations were started at this place with the specific aim of identifying the western wing of the monastery, and thus determining the former extent of the complex. However, the stone wall that has come to light is in all likelihood a partition wall of the southern wing, so our initial question was not answered. Nevertheless, we can have a reasonable idea of the location of the west wing, since in 2010 Pál Rainer identified the stone walls of a medieval building which fit well into the layout system of the walls and the geophysical measurements compiled recently. If our hypothesis is correct, Rainer's walls already mark the western end of the church on the north side of the monastery. Alternatively, these walls could represent the northern end of the western wing of the monastery.

Tűzvész a monostorban (9)

Fire in the monastery (9)

Fire in the monastery (9)

A monostorban folyt építkezések menetére minden bizonnyal döntő hatást gyakorolt egy nagy tűzvész a 13. század végén. Egy 1348. évi oklevél szerint a tűz nemcsak az apátság okleveleit és egyéb kincseit pusztította el, de az épületekben is komoly kárt tett. A feltárások során egyértelmű jelei mutatkoztak az épületek leégésének, a leglátványosabbak éppen itt, a déli szárny keleti helyiségében: helyben elszenült deszkák vagy gerendák, megégett edények, elszíneződött kőfalak. A tűz nyomai a monostor különböző pontjain azonban legalább három különböző korban végbement pusztításról tanúskodnak. Így egyelőre nem tudjuk biztosan meghatározni, hogy a szerzetesi épületszárnyak kőfalazatú kiépítése még a 13. század végi nagy tűzvész előtt megtörtént, vagy éppen e tűzeset tette szükségessé a nagyszabású kőépítkezéseket.

Fire in the monastery (9)

A great fire at the end of the 13th century certainly had a major impact on the progress of the monastery's construction. According to a charter of 1348, the fire not only destroyed the abbey's documents and other treasures, but also caused serious damage to the buildings. The excavations revealed clear signs of the burning of the buildings, the most visible being right here in the east room of the south wing: boards or beams burnt in situ, burnt pots, discolored stone walls. The traces of fire in different parts of the monastery, however, testify to destruction at least three different times. It is therefore not yet possible to determine with certainty whether the construction of the monastic wings with stone walls took place before the great fire at the end of the 13th century or whether it was this fire that made large-scale stone construction necessary.

Beszédes falsarok (8)

If only walls could talk (8)

If only walls could talk (8)

A 2022-2023. évi feltárások során kezdetben nem volt egyértelmű a felszínre került falmaradványok értelmezése. A kulcsot az ezen a ponton derékszögben beforduló, két oldalról kőfalakkal határolt folyosó jelentette. A folyosó alatt feltárt temetkezések, valamint a folyosóhoz kívülről csatlakozó épületszárnyak árulták el, hogy a középkori monostor kerengőjéről van szó. Az itt megtalált falsarok a kerengő egy késő középkori átalakításának emléke. A falat minden bizonnyal az udvarra néző nagyméretű ablaknyílások vagy árkádok törték át. Építése idején a monostor helyiségeit belülről fehér meszelés borította, az épület külső homlokzatait azonban fehér vakolatra felvitt vörös sávos festéssel (kvádermustrával) díszíthették. A monostor és temploma egyes épületrészeit kőfaragványokkal, másokat formába nyomott, fehér, vörös és fekete festésű idomtéglákkal hangsúlyozták. A vasrácsos ablakok kőből faragott kerettöredékei mellett előkerültek az üvegezés alkatrészeként használt kis ólomsínek is.

If only walls could talk (8)

During the excavations of 2022-2023, the interpretation of the excavated wall remains was initially unclear. The key was a perpendicular corridor, bordered on two sides by stone walls. The burials excavated below the corridor, as well as the wings of the buildings that connected to the corridor from the outside, revealed that it was the cloister of the medieval monastery. The wall junction found here is a reminder of a late medieval alteration of the cloister. The wall was most probably pierced by large window openings or arcades overlooking the courtyard. At the time of its construction, the interior of the monastery was covered with whitewash, but the exterior façades of the building may have been decorated with red stripes (ashlar detailing) painted on white plaster. Some parts of the monastery and its church were accentuated by stone carvings, others by terracotta bricks painted in white, red and black. In addition to the stone-carved frame fragments of the iron-grated windows, small lead calms as evidence of the glazing have also been found.

Évezredek hagyatéka a padló alatt (7)

A legacy of millennia under the floor (7)

A legacy of millennia under the floor (7)

A kedvező természeti adottságokat tekintve nem meglepő, hogy a bencések megtelepedését megelőzően a korábbi évszázadok, évezredek emberei is nyomot hagytak a területen. A kerengő legkorábbi középkori padlószintjei alatt különféle beásások foltjai mutatkoztak az agyagos réteg felületén. Az így kibontott gödrökben és oszlophelyekben többezer éves cseréptöredékek láttak napvilágot. Néhány éremlelet a helyszín római kori hasznosításáról tanúskodik, míg egy szép, bronzból öntött indadíszes kisszíjvég egy késő avar kori (8-9. századi) közösség jelenlétét sejteti.

A legacy of millennia under the floor (7)

Given the favorable geographical conditions, it is not surprising that before the Benedictines settled in the area, people from previous centuries and even millennia left their mark. Below the earliest medieval floor levels of the cloister, various marks have been found on the surface of the clay layer. The pits and pillar holes thus excavated revealed pottery fragments thousands of years old. Some of the coins are a testament to the Roman use of the site, while a fine bronze strap-end with tendril motifs suggests the presence of a Late Avar-age (8th-9th century) community.